Ferrari Elettrica is now Luce

History will record this as the moment when Ferrari asked the iPhone's designers to bring back touch

We still haven't seen the car. Ferrari has revealed only the interior of what will become its first fully electric production model, now known as the Luce - meaning light, and pronounced Lu-ché. And as someone who has spent years instinctively reading a Ferrari first through its stance, proportions and promise of motion, beginning the story from the inside feels quietly unfamiliar. Historically, that would seem like an incomplete introduction. With most Ferraris, the exterior is the opening line. Here, the narrative begins inside the cabin, in the way the driver is expected to interact with the machine. Ferrari has often spoken about the human-machine interface, but this time the focus runs far deeper.

The company has already offered a low-down on the electric heart that will power the Luce. Yet the decision to reveal the cabin before the car itself says something about the moment Ferrari finds itself in. Electrification does not simply replace an engine with a battery; it changes the entire sensory framework of driving. Sound, vibration and the subtle mechanical cues that once formed a constant background to the Ferrari experience begin to fade. When those signals disappear, the relationship between human and machine must be rebuilt in other ways. What Ferrari appears to be exploring first is not speed, but the connection.

To do that, the company has turned to an unusual set of collaborators. Alongside its engineers and automotive designers sit product thinkers more commonly associated with the modern consumer-technology landscape - most notably Jony Ive and Marc Newson of LoveFrom, whose work helped define the physical and emotional language of devices like the iPhone. It is an intriguing partnership, and not only for the obvious reason that I spoke of in my column previously - that cars are increasingly becoming software-defined devices. What makes it genuinely interesting is that Ferrari does not seem to be following the path that those devices established.

The arrival of the iPhone fundamentally altered how we interact with objects - and by that I mean not just the phones. Physical keyboards disappeared, buttons dissolved into glass, and the reassuring click of a mechanical action gave way to smooth, silent touch. The trade-off made sense: fewer moving parts, cleaner surfaces and simpler interfaces. Over time, this philosophy spread far beyond phones. Home electronics, appliances and eventually car interiors have adopted the same logic. Screens have multiplied, infotainment systems have become control centres, and the interaction itself has grown increasingly abstract.

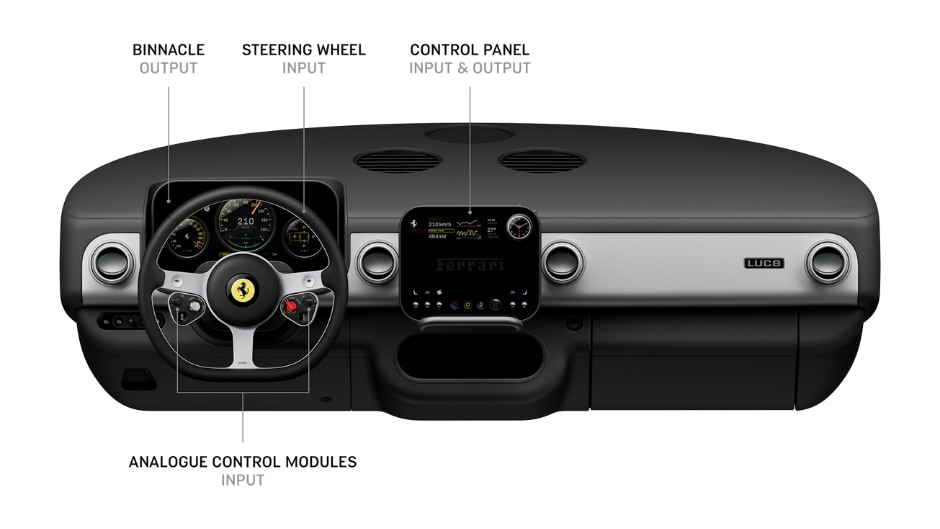

Ferrari's early look at the Luce suggests a subtle resistance to that phenomenon. Instead of leaning fully into the screen-dominated approach that defines many modern cabins, the interior appears to reintroduce tactility - physical controls, material richness and interactions that provide confirmation through touch rather than animation alone. This is not nostalgia in the conventional sense. It feels more like an acknowledgement that, in an electric performance car, tactility may become newly important. Perhaps that very focus on touch is what makes the rest of the cabin appear so plain and familiar - uncannily similar to the device you are probably reading this story on.

A combustion engine constantly communicates with its driver. Even at steady speeds, there is a background conversation made up of sound, vibration and rhythm. Electric propulsion, by contrast, is composed and distant. Its refinement is technically impressive, but it removes layers of sensory information that drivers once processed without conscious thought. Replacing that information does not necessarily require artificial soundtracks or theatrical effects. It may instead require something far simpler - interfaces that feel real to the touch.

This is where Ferrari's collaboration becomes especially telling. Designers who once helped usher the world towards seamless touchscreen interaction now appear to be participating in a project that restores a measure of physical engagement. There is irony in that reversal, but also logic. As technology matures, the pursuit of pure minimalism often gives way to a renewed appreciation for texture, resistance and material presence. Luxury, after all, is rarely defined by absence alone.

None of this answers the central question that will ultimately matter. How the Luce drives - how it accelerates, steers and communicates at speed - remains unknown. Ferrari's identity has always been secured on the road rather than in the studio, and that truth will not change simply because the powertrain has. Yet interiors shape expectations. They hint at priorities. They reveal what a company is trying to preserve when everything else is being reinvented.

What the Luce's cabin suggests, at least for now, is that Ferrari understands the risk of allowing electrification to become purely clinical. Performance numbers alone cannot sustain emotional connection. Nor can flawless digital interfaces. If the future Ferrari is to remain meaningful, it must still engage the senses that survive the transition away from combustion. Touch may prove to be one of the most important of those senses.

There is a quiet confidence in beginning the story here. Before showing us speed, Ferrari is showing us intent. And intent, more than technology, is what usually determines whether a turning point becomes a loss - or the beginning of something that still feels unmistakably, Ferrari.