Hybrid theory: 24 Hours of Le Mans technical changes for 2014 explained

The year 2014, be it Formula 1 or Le Mans, is all about the Energy Recovery System or ERS. The ERS, simply put, is a method to harness energy which would otherwise get dissipated in the form of kinetic or heat energy and the like, and use it to accelerate the car whenever required. This system has emerged as a collective effort from the automobile industry to improve the efficiency of vehicles by making internal combustion engines more efficient in burning fuel, and bolting on turbos and electric motors to eke out as much juice as possible. ERS takes this trend to the next level by making the cars even less reliant on the fossil fuel, every lap of the race.

Audi might just have to run for cover with Porsche and Toyota's hybrids out to get them this year

Audi might just have to run for cover with Porsche and Toyota's hybrids out to get them this year

And the legendary 24 Hours of Le Mans is not new to hybrids though as the organising body, Automobile Club de l'Ouest (ACO) drafted the regulation to include them in 2009. Three years later, a hybrid car in the form of the Audi R18 E-Tron Quattro won Le Mans, and this was the very year that made experts get down to formulating rules for 2014, which looks to bring a sea of change in the manner in which this sport is run.

Le Mans is different from Formula 1 in one important aspect - the car not necessarily equipped to be the fastest, but with the most energy efficient and reliable package, wins the race. The reason this series is referred to as Endurance Racing is because the car and the driver have to endure whatever the track throws at them for a good 24 hours. This is why, even though the ERS features rather prominently in F1 too, the method of its deployment is majorly different in the case of Le Mans.

The rule changes that feature the use of ERS are primarily focused on the premier LMP1 class. Every motorsport follower will recognise this category as the long-standing battle ground between the technology-laden Audis and the rest of the world. Peugeot challenged them briefly and so did Toyota, with equally tech-packed cars. However, this meant massive expenditure on their parts, and as a result, private players with smaller budgets and simpler cars were just filling up the grid. Also, Audi winning most of the races was robbing spectators of all the fun of close racing. That's when ACO decided to sort this out by introducing rules to ensure a level playing field among all, without diluting the fun of the sport or cutting down the technological ingenuity the sport demands. This resulted in the idea of allowing each car a fixed amount of energy per lap.

How this works?

A contradictory ruling by the ACO in a quest for energy saving is de-restricting the cap on engine capacity from the previous year, which used to be 3.4 litre for gasoline and 3.7 litre for diesel powered cars. Further in this direction was the relaxation of restraints on the turbochargers, superchargers, air inlet restrictors etc. This time, they've even allowed variable geometry turbos. Of course this is good news for all the racing fans, but again, how then, is ACO helping save energy?

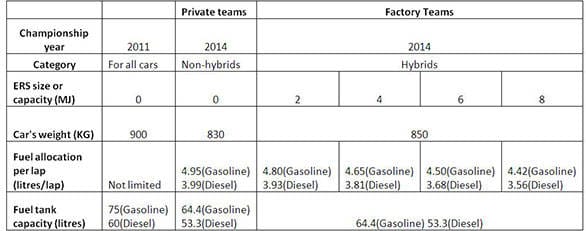

Well here is the catch. The cars will be allowed to consume limited amounts of fuel per lap, that is 3.99 litre for diesels and 4.95 litre for gasoline-powered cars, the fuel consumption being measured by homologated fuel-flow meters. All non-hybrid privateers in the LMP1 class have to adhere to these limits. Also, for privateers the engine capacity is limited to 5.5 litre for cost saving. Factory entries are to conform to further restrictions - they are required to compulsorily enter the hybrid ERS cars which are divided into four categories as per energy produced (measured in mega joules MJ) by their ERS system, i.e. 2MJ, 4MJ, 6MJ and 8MJ. Refer to the table* below for a better understanding of the ruling.

*All the figures above are for one lap of Le Mans circuit.

The table illustrates that for one lap, a non-hybrid car can use more fuel than a hybrid car. The hybrid has to make up for restrictions on fuel consumption by deploying its ERS system as and when required. This creates parity in performance between the factory and private entries, giving the latter a fighting chance against the big factory players.

Factory teams are allowed to choose from any of the four ERS capacities as per their convenience. It will be interesting to see how different factory teams will be racing each other with different ERS systems in their power trains, especially when Porsche are entering their own LMP1 challenger, the 919 Hybrid this year, and Toyota are entering with their challenger, TS040 Hybrid.

The Audi R18 e-tron is the most complex piece of machinery built by Audi yet. Its system is similar to the ones used in Formula 1 one motor generator unit (MGU), placed in the front axle, recuperates energy during braking, and the other MGU sucks energy from the hot exhaust gases through a turbine running motor. Both these MGUs store energy within a flywheel accumulator system (where, instead of a battery, a very fast spinning flywheel stores kinetic energy) and the driver can harness that as and when required. The engine is an evolution of last year's 3.7-litre V6 TDI turbo.

Porsche has a 2.0-litre four cylinder petrol turbocharged engine producing north of 500PS. This car uniquely extracts energy from the waste exhaust gases which are generally by-passed from the turbocharger through a waste gate valve. This gas spins a turbo, which is connected to a motor charging a lithium-ion battery, thus powering an electric motor in the front axle when required. The motor in the front axle also recovers energy during braking.

Toyota, on the other hand, is using a petrol powered naturally aspirated 3.4-litre V8, with a hybrid system consisting of motors both on the front and the rear axle, and a super-capacitor as energy storage.

The cars are said to produce around 800 to 1000PS, as a result of the combined efforts of the engine and the ERS. Even though Toyota's system seems to be the least complicated, they've won the first two rounds of the WEC in the Six Hours of Silverstone and the Six Hours of Spa. Porsche in their first season of the WEC bagged a third place at Spa, standing second in the championship, while Audi finished a dismal third in Silverstone and second in Spa.

The system once selected by a manufacturer (private or factory) cannot be changed for the rest of the season. The cars will be using next generation bio-fuel E20 for better control on emissions. With these systems in place, manufacturers are claiming energy saving of up to 30 percent as compared to the cars of 2011 and 2012. Use of exotic materials for engine manufacturing is banned as are electromagnetic valves, thus bringing down costs further.

What about body work and aerodynamics?

The biggest change in this regard is that all the cars this season onward will have closed cockpits, thus reducing drag and ensuring improved safety for drivers. To improve the visibility and reduce accidents, the driver is required to sit further forward and higher as compared to the previous year. The height of the front wing is reduced to further aid safety.

Overall width of the car has been brought down from 2000mm to 1900mm to reduce drag and improve efficiency. The front aerodynamic is adjustable for better aero balance and the wings will have new position of holes on it to make the car more stable as a result of reduced drag.

All these changes are expected to allow close racing without compromising the technological development in the cars. The regular vehicles, for example, are developed from the technologies tailored down from such racing series. Up till last year, apart from the spectacular Audi R18, the real thrill of close racing was provided by the wheel to wheel racing of the GT Pro and Am cars. It will be interesting to see if the new LMP1 cars can turn the tide to their favour this season.