A letter to Stefan Bellof

Dear Stefan,

This wasn't meant to be a letter to you, but that's how it turned out. And if there's one thing that I learned during my visit to your hometown Giessen one rainy December afternoon, and also from the conversation I had with your brother Georg, it was that life doesn't always turn out the way we plan for it to. So, instead of the straightforward prose that I was expecting as a result of this conversation, I have this letter instead. Like I said, it's just the way things turn out sometimes.

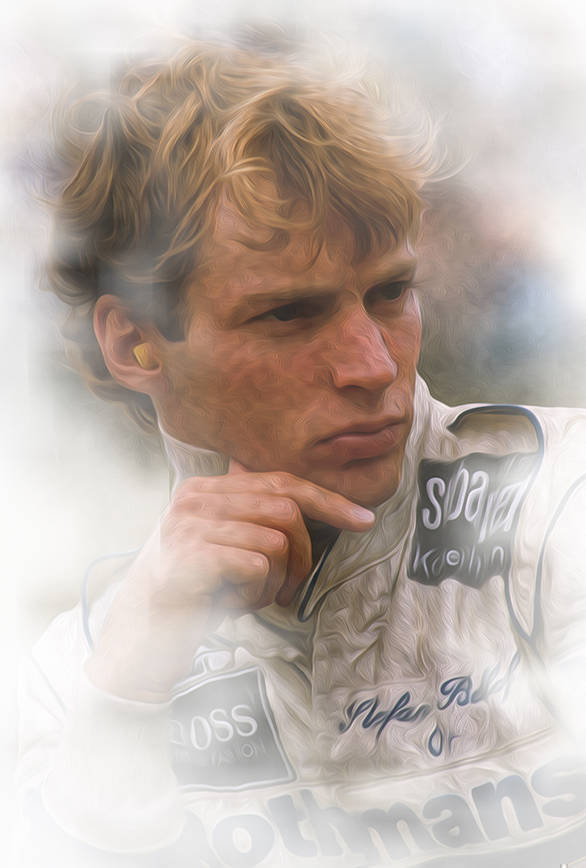

Stefan Bellof in his Rothmans Porsche overalls

Stefan Bellof in his Rothmans Porsche overalls

I think you should know that I first heard of you years after you were already gone. You see, I was only born two years after your fatal crash at Spa Francorchamps on September 1, 1985. So it was a good while after, that I first read about you in a nice big fat tome on Formula 1. You were introduced as the king of the Nurburgring, because, even though this happened in the World Endurance Championship, your lap record of 6 minutes 11.13 seconds during qualifying around the old Nordschleife, is still what most people remember you for. When I read about it those many years later, that lap record was untouched. Today, as I sit here writing this, 33 years after you blistered around that legendary track in your Porsche 956, that record is still unbroken. It might just stay that way. If it does, it will be nice. Because there are some things, every once in awhile, that should remain untouched. It makes the rest of the world aspire to something. Legends sometimes really are important.

So, you can imagine, growing up reading about someone such as yourself, I was in awe. I had decided early on that when I finally became a motorsport writer, I'd get around to doing a few stories that were special to me. One of those stories was to go to Giessen and wander around until I met someone who knew you when you were young. And then we'd sit and chat about you and your motorsport career and we'd discover a great many things. Well, I didn't go and wander around until I ran into someone who knew you. Instead, one cold September afternoon, I found myself writing out an email to your brother Georg, asking him whether he'd let me come by to his house and allow me to interview him. You can imagine that receiving such a request from a total stranger wasn't something that he was entirely comfortable with. So, it took some amount of persuasion and persistence on my part. But he finally gave in. And those longed for discoveries were made after all.

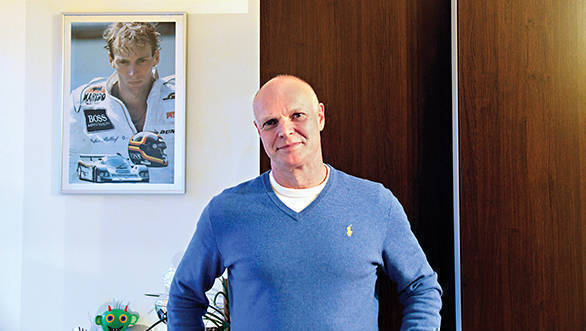

Georg Bellof in his home in Giessen, with a photo of his brother Stefan hanging behind him

Georg Bellof in his home in Giessen, with a photo of his brother Stefan hanging behind him

It was raining the day I got to Giessen. And while I was prepared for the rain, I wasn't prepared for a good many other things. Like that fact that Georg, standing there on the porch in a light blue sweater, would be as welcoming as he was. Or that he'd look so much like you. It isn't obvious at first, but there's definitely family resemblance. You've got the same eyes. I'm not sure whether you've got the same laugh, but boy does Georg, or 'Goa' as he tells me he's called, have a good laugh. It makes interviewing him about what is obviously a rather difficult topic for him to speak about, just a little easier.

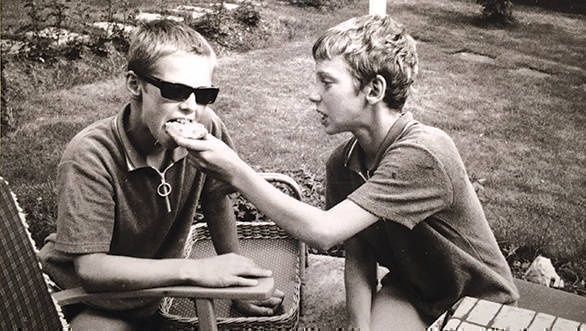

We start with the old days. Stories of how he learned to drive when he was six years old. You would have been five, given that you were a year younger than he was. The two of you really couldn't see above the steering wheel of the cars that you were driving, but it didn't matter. Drive the Bellof brothers did. Then he tells me about the first go-kart that you'd ever had, the one that your grandfather bought you two from a fair. And how you stripped it bare, throwing off the bumper and absolutely anything else that you didn't need, to save weight and to go faster. Of course, it's no surprise that the two of you started racing soon after that. But, it isn't really how you started racing that we want to talk about. Here's why

There are some stories that must be told backwards. If you look at them from beginning to end, you might miss the point of it all. When you look at them from the end to the beginning, then they make a little more sense. I think this is true of your story.

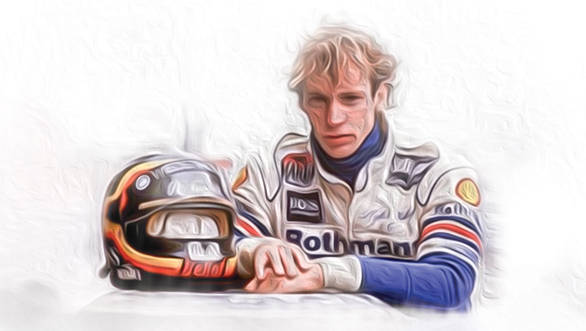

Stefan in the Brun Motorsport Porsche 956, the last car he'd ever race

Stefan in the Brun Motorsport Porsche 956, the last car he'd ever race

Georg tells me that he was in the car when he heard about your crash at Spa. The funny thing is that he never switched the radio on when driving. That day, for some strange reason, he did. And he heard the voice of a man talking about this heavy crash that had happened at the 1,000km of Spa to a driver named Bellof. By the time he got home, the phone was ringing and there was the manager Peter Reinisch on the line, trying to play the whole crash down and make it seem like it wasn't as bad as it had been. But he says that when he saw the video of how your Brun Porsche 956 hit the barriers head on, he knew it was over. He knew that nobody could survive a crash like that.

Georg also tells me that it was true you didn't want to race that weekend. By that time you were already a Formula 1 driver, one who was going places that too, and you weren't racing sportscars on a regular basis. But, since that particular race was Thierry Boutsen's home race, and a race that he really wanted to win, you'd made the exception. There were these little events that occurred before the race which I suppose can in retrospect appear to be premonitions. Like your Bitter breaking down on your way to the Frankfurt airport, and Georg driving you there instead. Well, at any rate, after you were done testing at Silverstone, Thierry picked you up and you flew to Spa with him. And then what happened, happened. Georg is philosophical about it. Because over the years he's come to accept it. He points out to me that there's always the other side. And that if you and Thierry had won that race, everything would have been different. He points out that Thierry blaming himself for coercing you into racing doesn't make any sense, because no one could have known what was going to happen. He says that no one could have known that on that particular occasion, Thierry would forget to switch off the fuel pump during the driver change, which meant that when you tried to start the car, it wouldn't start. That when you finally did get the car started, that no one could have predicted that the pitlane light would be red, which meant that Jacky Ickx, your rival, was out free on track after his pitstop, while you sat there seething in your car. He says that he was sure you were fuming, because he knows you. He says that he knows you weren't happy with the situation of that race, and that you were likely unhappy with the way that Ickx blocked you all over the track. And that when he opened up a little bit of a gap, you thought you could dive in and overtake him. Then there was contact at Eau Rouge. One life ended. Other lives changed. The world was a little bit different after that. Collisions, celestial or otherwise, have a way of altering the Universe forever. And so it was that day at Spa.

The rain-soaked Monaco GP in 1984 that could have been a potential win for Bellof, had it not been for the race being red flagged

The rain-soaked Monaco GP in 1984 that could have been a potential win for Bellof, had it not been for the race being red flagged

It wasn't the first clash that you'd had with Jacky Ickx. He'd been a pretty big influence in costing you your first Formula 1 win. It was that race at Monaco in 1984. Of course, I know that the world goes on about how Ayrton Senna would have won the race, had it not been red-flagged by race director Ickx because Alain Prost kept pointing at the sky every time he crossed the start finish line to indicate that there was too much rain and therefore conditions were unsafe for racing. But Senna was faster than Prost, which meant he would likely have caught and passed him. You were as fast as Senna, which meant that you could have also challenged for the win. As things stood, when the chequered flag fell, it was Prost who won the race in a turbocharged McLaren, Senna who finished second in a turbocharged Toleman, and you, third, in a naturally aspirated Tyrell. That later on in the season Tyrell's results from that race would be erased is another story. But after that performance, where you even managed to get past Ferrari's Rene Arnoux, the world really took notice of you. Ken Tyrrell often joked that he didn't need a turbo because he had you, Georg says. And Enzo Ferrari wanted you to drive for him - the contract had been signed for 1986 before you crashed at Spa. You were, they said, a future world champion.

The Bellof boys when they were still lads racing go karts

The Bellof boys when they were still lads racing go karts

In fact, Georg says that you'd decided that your singular goal in life was to be Formula 1 world champion. And with that goal in mind you did everything. That's why you did as many racing series as possible all in one year, and that's how you moved from Formula Ford to Formula 1 in just four years. It was the stuff that dreams were made of. But Georg said that you didn't just dream. That you had the sort of self belief that was required to follow through on those dreams. And that's what made you so special. I think it also helped that you had the sort of support system that helped make you successful. When Georg gave up on racing after Formula 3, he focussed his energies on helping you. Of course, your natural talent and determination counted immensely. It also made you popular with the mechanics, and probably somewhat unpopular with your team-mates. He says you'd watch onboard footage of your team-mates sometimes and say "Why he is lifting off, that part of the track is flat out!". Yes, you certainly ruffled a few feathers when you, as a relative young 'un, just sauntered into the paddock and showed the old hands how it was done. Most of them didn't like it. Some, like Hans Joachim Stuck are grateful to you to this very day. 'Stuckie' your brother says, still declares that he's thankful to you for teaching him how to drive the ground effects cars. I've seen him say that in an interview myself. I wonder what that must have been like, to teach an experienced racer a thing or two about racing. If you hadn't crashed at Spa, the chances are that you'd have taught more people a thing or two about racing. What with that Ferrari contract and all. But we'll never know

Best remembered as a rising German racing star, is Stefan Bellof

Best remembered as a rising German racing star, is Stefan Bellof

We'll also never know 'why'. I've been reading some Kurt Vonnegut of late. There's a line in Slaughterhouse Five that talks of how 'Why?' is such an 'Earthling question'. And it's true. There's no point analysing why some things happen. They just do. Your brother says the same thing. He says that at the end we all ask, "Why, why, why?" We ask, "Why did this happen to me?" or "Why did I do it?" But he also says, "In the end it doesn't really count." Like he says, we could step out of our houses and something could fall on us, and that would be the end of it. It's a little like Michael Schumacher surviving years and years in one of the most dangerous sports in the world, and then meeting with an accident, that he doesn't appear to be likely to recover from, on a skiing holiday. The reasons don't count.

Which is why I'm so determined to look at it all backwards. If I look at your story from the day you started karting to the day you died, I'd see the story of a young man who didn't make it to his goal of being Formula 1 world champion. That makes me sad. And I don't think anyone should be sad when they think of you, because you've done some pretty terrific things in your career. When I look back at your journey, from the day you crashed, to the day you first sat in a go-kart, it's everything else that stands out. I see the contract you got with Ferrari after such a short time in Formula 1. I see the World Endurance Championship title that you managed to win in 1984. I see the determined young racer who wore his brother's fireproof overalls in his first competitive Formula car outing, managing to lead the race at several points. I see a racer who had no money, but heaps of talent. And I see a racer who refused to take no for an answer and got to places based on that talent of his. And that, to me, is your single biggest achievement. Because there is tremendous justice in the world when people achieve things on merit and merit alone. It gives the world, in cynical times, reasons to believe in hard work, determination and focus. It gives the world reasons to believe in having dreams, converting those dreams into goals, and then blazing right after them. And it gives every single person in the world a darned good reason to believe in himself.

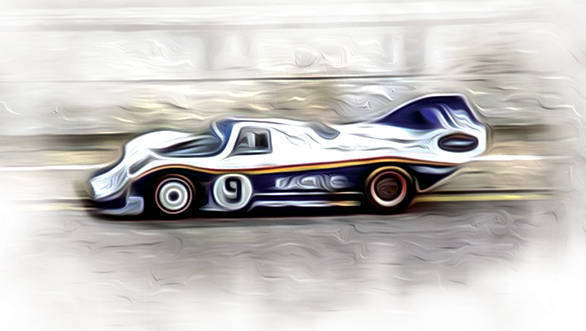

The Rothmans Porsche with which he won the 1984 World Endurance Championship

The Rothmans Porsche with which he won the 1984 World Endurance Championship

I'd always imagined that when I did eventually make it to Giessen, I'd visit your grave. Or that when I'd go to Spa-Francorchamps, I'd visit the corner of your crash. But then when I spoke to your brother, I realised that putting flowers on your grave or at a corner, that was never meant to be my pilgrimage. But this little letter to you, this comes as close as I can get to making a gesture of remembrance. You should know that this letter wasn't easy to write, because this pilgrimage ended up being more than I could have asked for. I set out to dig up a few motorsport memories. Instead, I got, through the words of the one person who probably knew you better than anyone else in the world, so much more. I got motorsport memories and a philosophy of life from your very wise brother. A philosophy of life that involves being prepared for everything you ever set out to do and never dwelling on 'why'.

I suppose it couldn't have been any other way.

- Vaishali

Illustrations: OVERDRIVE